The advantages of resilience over robustness

Europe is ageing. While this is good news, as Europeans live longer, healthier lives, it is also going to challenge our institutions: the labour market, pension systems, families, communities. Often, the hope is to “fix” demographic change. Usually this is imagined in a very specific way: raising fertility rates.

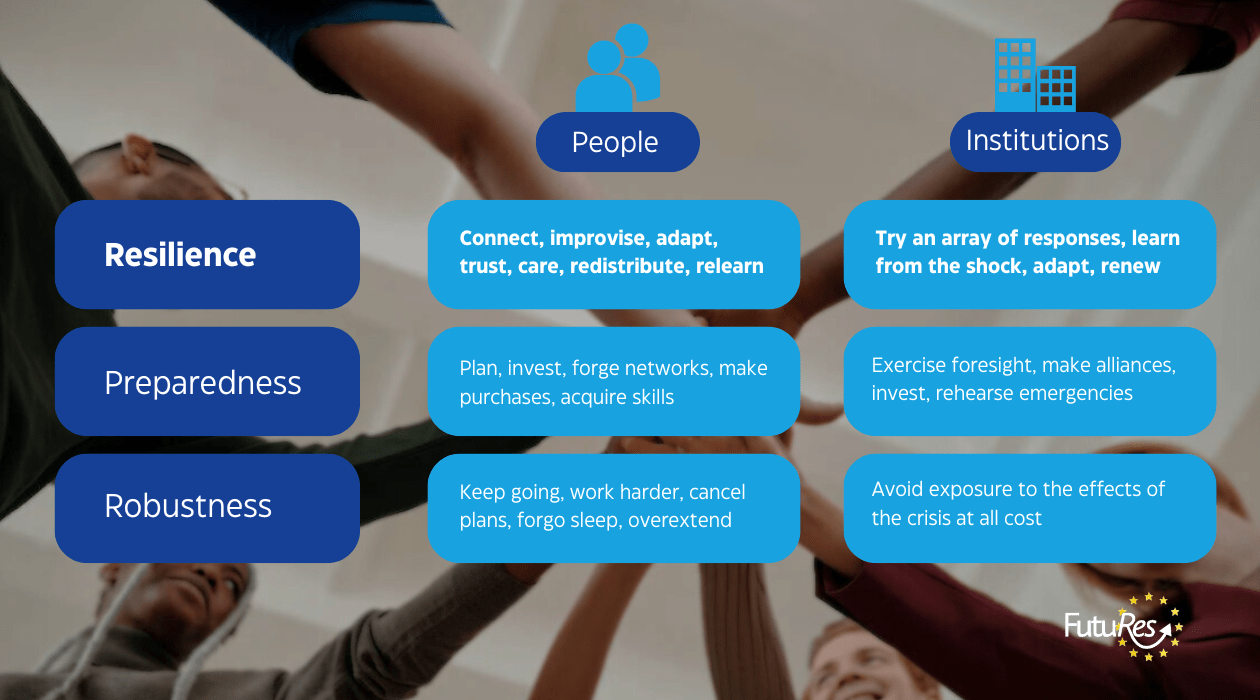

This is an understandable thought, since Europe’s Ageing is driven in part by low fertility. However, the call for higher birth rates is a response influenced by the principle of “robustness”. Instead, we need a response of “resilience”. What is the difference?

Robustness is about shielding against any shocks or disturbance that might come our way. The problem is: we don’t know of which kind (or when) the next shock will be. Who could have predicted the Covid-19 pandemic?

Robustness is also about trying to bounce back to normal in case of disturbance to the way things were. In other words, robustness means to minimize shock by avoiding exposure to whatever causes discomfort and negative consequences. An understandable response. But systemically, it is not the most efficient approach. Robustness can be tiring, ineffective, and it can hinder productive change.

For example: demographic projections have shown for years, that there is no “quick fix” to societal ageing. Raising fertility with a set of simple policies clearly does not work, as FutuRes family policy expert Prof. Anna Rotkirch shows. At the same time, migration can help with the strain on labour markets, but the effect is limited, as we can learn from FutuRes migration expert Prof. Jakub Bijak. Holding on to the idea of “reversing demographic change” is costing valuable time and resources.

The goal should be to adapt, to transform. This is a response in the spirit of resilience. FutuRes has conceptualised the meaning of resilience to be a counterproposal to “robustness”. There are two academic traditions supporting this view: psychology understands individual resilience, ecology understands systemic resilience. In the project, we have integrated these two strands to conceptualise societal resilience in demographic change.

Why an institution should never be only “robust”

Let’s imagine a crisis situation. There are three principles of response: robustness, preparedness, resilience. All are valuable. However, the deciding factor is uncertainty. In a world where challenges arise predictably and periodically, robustness might suffice. However, the more systems are faced with the unexpected shocks, new developments and multiple crises, the more they need resilience.

What are we aiming for? What we need is to create virtuous circles of resilience on all levels: a resilient community will create resilient people. Resilient institutions will create resilient policy responses.

What does this mean for intergenerational fairness?

• The most resilient institutions tend to be those where we spend time during the ages 25 to 65: organisations of work and business. We see very little flexibility in institutions where younger and older people are: places of education, and places of long-term care. This means that these groups are hit much more severely by shocks, as we have seen during the pandemic.

• Fairness is created across the life course. So is unfairness. We already see that the increase of life expectancy is not the same for everyone, but indeed, living longer is becoming more unequally distributed by socio-economic class. At the same time, we project a large risk of worsening gender inequality when it comes to pensions. This inequality is a product of unequal opportunities in early education, work life and during periods of caregiving. To invest in intergenerational fairness for the future is to prioritise Europe’s young people: to expand their resources for resilience and their chances to age better.

This means adapting around the new needs which present themselves in this transition: more need for long term care, the need to work longer where possible, for new pension systems, the need of support for depopulating communities, the need to rethink the legal frames around family and kinship.

Let us be clear: Resilience is not easy. Embracing change is difficult and changing one’s beliefs can be challenging. In order to avoid putting the burden of transformation solely on individuals, Europe’s institutions should aim to act as role models.

Values of institutional crisis resilience

1. Redundancies: Instead of planning for one crisis response (in the spirit of cost-efficiency), plan for several options of responding to unexpected crises

2. Exposure: An institution which constantly aims to protect itself from exposure to shock in the name of safety, will likely fail to achieve resilience. It might get better and better at coping with the usual, but more and more vulnerable to the unexpected.

3. Modularity: The institution entertains a strong network beyond its walls. Strength here comes not necessarily from size, but diversity: This network is made up of a diverse mix of expert voices and perspectives, rather than a large number of similarly-minded ones.

4. Reaction time: Horizontal organisation is beneficial for more speedy reactions

5. Readiness to transform: To see that the idea of a quick fix (such as raising birth rates) is often a fallacy

6. Managing across scales: An institution manages to both focus on its mission, but also is aware how that mission is situated within the bigger picture.

This article is based on a presentation held by FutuRes Head of Research Prof. Arnstein Aassve at the FutuRes March 2025 Stakeholder Dialogue

Further reading

Chłoń-Domińczak, Agnieszka & Anna Maliszewska (2024): Fertility decisions in crises: Policy lessons from COVID-19 and the Great Recession, Population Europe Policy Insights.

Aassve, Arnstein: "Most people would be equally satisfied with having one child as with two or three – new research", The Conversation.

Rotkirch, Anna (2023): "Ten steps towards a baby-friendly Europe", Population Europe Policy Insights.

Header image: Diva Plavalaguna