How robots will change our jobs

It may be difficult to imagine today, but idea that “robots will take our jobs” used to be met with optimism. The idea was that automation would enable us to work less and enjoy leisure. In the 1980s pessimism began to rise as automation became a reality. Forty years later, we human workers are still here, and jobs still require people.

What is certain though, is that jobs will continue to change. Moving forward, people will work with robots at their side more than ever.

In my latest research for the FutuRes project, I looked at how automation will impact jobs. Specifically, I analysed jobs that require different education levels. I am doing this so that policy can plan to adapt for this changing labour market - in a fair way, for everyone in society.

My research shows that education (or skill level) is somewhat of an indicator for the likelihood that a job might be automated. For instance, jobs that require higher skills typically need more specialism and creativity. Meanwhile, many jobs that are considered low-skill are highly repetitive, and could more easily be automated.

However, neither skill nor education level are perfect indicators of future job automation! I explain some of the nuances below. The examples I give of jobs come from a 2017 study by Carl Frey and Michael Osborne (see "further reading" at the end of the page).

What will happen to high-skilled professions?

Highly educated and skilled workers are invaluable to labour markets, as their expertise makes them productive in their own field. Meanwhile, expertise also enables them to adapt and transfer skills to other fields that are in higher demand.

This means that partial automation could allow, for example, software engineers who specialise in finance to transition to professions in AI or cybersecurity. Meanwhile, medics, teachers, lawyers or archaeologists are the types of jobs in this category that are among the least likely to be fully automated as they require applied knowledge, dexterity, and ethics.

On the other hand, some jobs that are currently considered “high-skill jobs” but have repetitive tasks may face “down-skilling” because of automation. Professions such as accountants, geoscientists or historians, if they have tasks such as data entry, document analysis, will likely be most affected.

This could lead to a reduced demand for people to fill these jobs; and/or to a shift, where people with intermediate levels of education will be able to perform these tasks with the help of automation.

Who is most vulnerable to automation in medium-skilled professions?

Labour markets (and societies) are mostly populated by jobs needing intermediate levels of education. Jobs in this category include skilled trades, health and social care, transport, manufacturing, as well as customer service or office work. Jobs especially in this category will evolve with automation; however, they won’t disappear.

After all, automation that does manual labour and computer work still requires human supervision - machines that do welding or AI that prepares financial accounts still needs humans to ensure safety, accuracy and to ensure they meet regulation requirements.

It's all about the medium-skill professions: Macroeconomist Emily Barker presents her FutuRes research on the effects of automation on labour. She speaks about how different professions are more or less likely to be impacted - and what policy can do to help people adapt.

Therefore, adapting and learning how to work alongside automation is imperative, particularly when it comes to computer and AI skills.

The most vulnerable “medium-skill jobs” to automation include jewellers, secretaries, or financial account preparers. These professions have high levels of repetition that can be automated; therefore, the number of workers required will likely decrease with automation.

AI may also down-skill some tasks in professions such as architecture, finance and software development, because of new tools that simplify processes. For example, app development no longer requires advanced knowledge of coding.

Saying that – not all medium skilled work is at risk to automation! The least vulnerable jobs require high levels of human interaction and/or dexterity, such as construction supervisors that require onsite visits, skilled trades people, such as plumbers, and nurses and carers. Such manual labour jobs can be made easier and less physically demanding with the help of robots or computer systems.

How are low-skilled professions affected?

Robots have long posed risk to “low-skill jobs” that require little to no education, especially when speed is the priority. If jobs involve repetitive tasks that are easily replicable by robots, (human) workers will be replaced when employers find it financially viable. For instance, much of the work at packaging warehouses or loading freight is easier, quicker and safer to do with machines.

Not all low-skill jobs are at high-risk of automation, however. Like medium-skilled jobs, there will be less automation in tasks that involve dexterity, reasoning and interpersonal interaction. For example, people are preferred to robots when it comes to care work, such as looking after children. Bailiffs are another, less vulnerable profession to automation, as well as concierges. While both of these jobs have a “human element”, both also have tasks that aren’t financially viable to automate.

Another example is fruit picking, because it requires dexterity. So far large-scale robotic systems have struggled to meet demands or match that of existing workers in this sector.

The varying needs of Europe’s member states

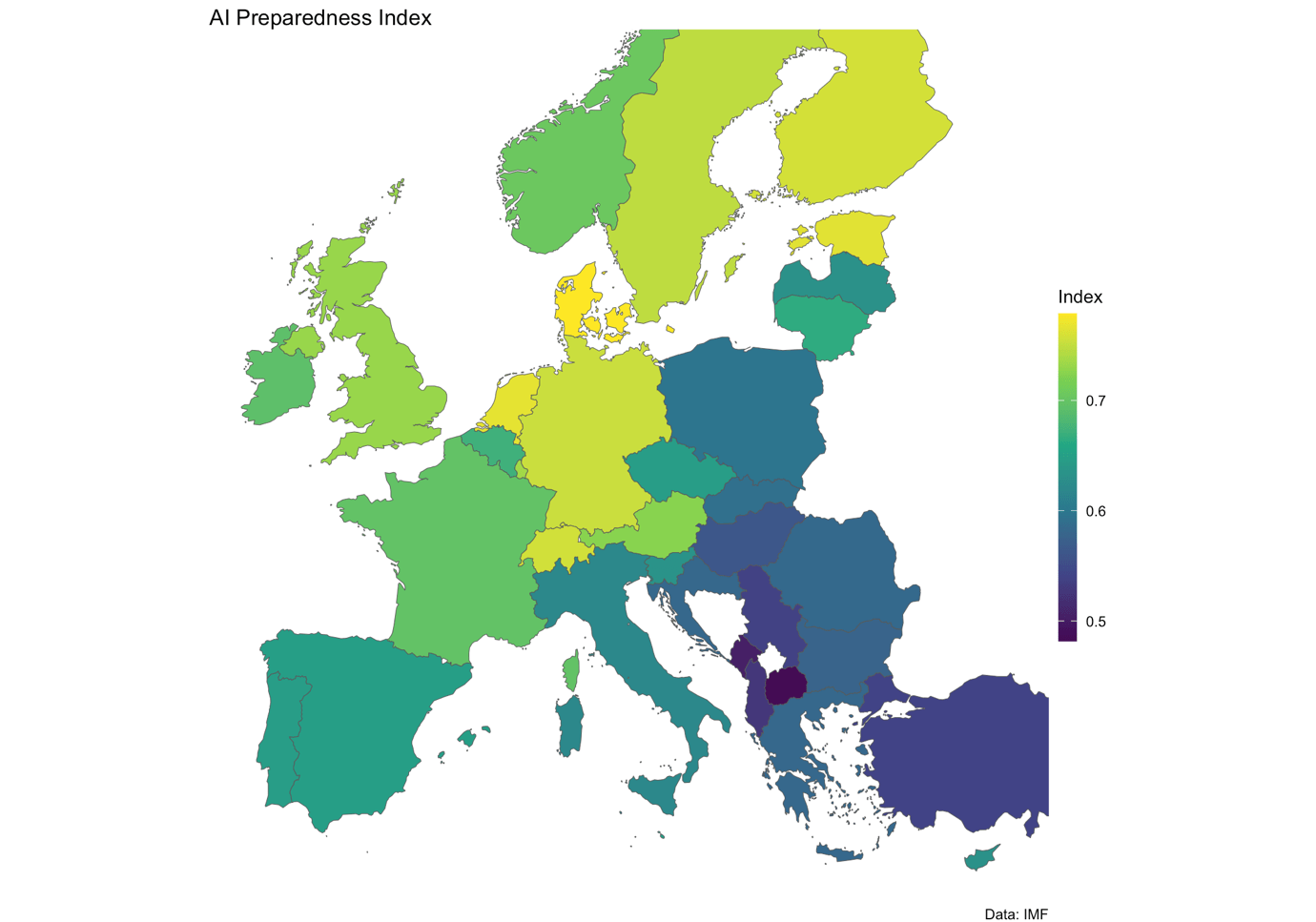

Understanding AI readiness is crucial for determining the impacts of automation on the labour market. Establishing the existing digital infrastructure and human capital highlights the opportunities and strengths of the existing market that can be improved and gaps filled, or where to target investment. Overall, we know that Europe is relatively prepared for AI compared with other regions of the world, according to the International Monetary Fund’s Index (see map below).

While there is diversion between countries in northern and western Europe (especially Denmark, rated as the most prepared) and those in the southern and eastern parts of the continent, seven of the top 10 countries in the world are in the EU27+, which provides an excellent foundation for the preparedness and expansion of AI in Europe.

The map shows AI Preparedness in Europe (IMF, 2023). Higher values on the index reflect higher AI preparedness.

One positive implication of high preparedness is that particularly for large countries like Germany, it will enhance attractiveness for highly educated tech professionals to immigrate and to fill existing labour market gaps. Furthermore, providing resources to develop AI can trickle down to medium and low-skill occupations too (as described above and further in our report). Some elements of AI have the potential to down-skill high-skill tasks to skilled medium educated workers, as discussed above. This provides a bias to the west and north countries who have a higher level of AI preparedness and a higher-skilled workforce.

In summary, the impacts of automation in Europe will vary by the skill level of jobs available in labour markets as well as its AI preparedness. These differences, along with country-specific industries, highlight the need for tailored labour and automation policies. Policymakers at the EU and national levels need to work together to make best use of their existing resources and specialties.

This article is based on a presentation given by macroeconomist Emily Barker, University of Southampton, in the Futures Policy Lab

Further reading:

Frey, Carl Benedikt and Michael A. Osborne (2017): The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?, in: Technological Forecasting and Social Change.

International Monetary Fund (2023): AI Preparedness Index (data retrieved in April 2025)

Image Source: bertellifotografia/pexels